As pranksters prowl for marks on April Fools Day, they might want to know how their punchline will land. It turns out that genetics plays a role not just in a person’s sense of humor, but in their ability to get a joke, according to data from 23andMe.

This is not a joke.

Indeed, like most traits, our sense of humor is influenced not only by genetics but also by environmental factors like upbringing, culture, and social circle. We can see this in 23andMe’s data as well, which shows regional and gender differences. For example, women rated themselves as having a lower sense of humor and ability to get jokes. This could have less to do with men having a better sense of humor and more to do with how women self-assess their humor. It could also reflect cultural norms that have even penalized funny women in the workplace and perpetuated the “women aren’t funny” myth.

23andMe also found that jokes land a little better in Illinois, home of Chicago’s humor mill Second City, than in the barren plains of North Dakota. Another place where they love to laugh—Washington D.C. No joke!

But there are also interesting genetic components to one’s sense of humor.

There may be evolutionary advantages to having a funny bone, and studies have looked at the genetics of the propensity to show positive emotional expression like laughing and smiling, and as well as the ability to get a joke and ‘mating success.’ For instance, humor helps establish social bonds. 23andMe researchers looking at data from customers who have consented to participate in research found interesting genetic associations with having a sense of humor that appear to center on brain development, cognitive function, and intelligence. One of the strongest associations we found for a person’s ability to get a joke was in a gene that is important for neurodevelopment and a major player in autism.

Scientific Details

So how did we do this?

We asked just over one million 23andMe customers who consented to participate in research the following questions:

- On a scale of 1-5, how would you rate your sense of humor? Answers included 1 (Below Average), 2, 3 (Average), 4, 5 (Above Average)

- How easy is it for you to get jokes? Answers included Very Easy, Somewhat Easy, Somewhat Hard, and Very Hard.

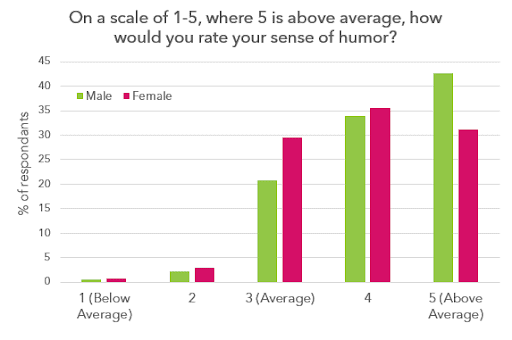

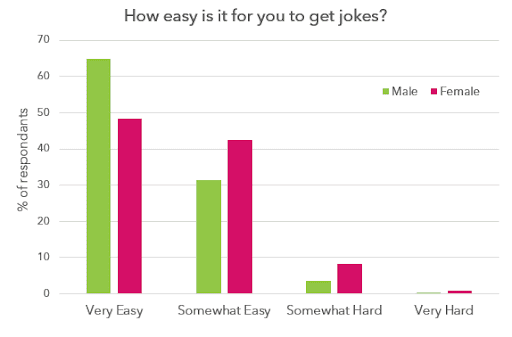

Before we delve into the genetics, let’s take a look at demographics where we saw the starkest differences: among the sexes. (As a side note about 70 percent of people assess themselves as being above average in having a sense of humor and only 5 percent say they are below average. This could be that people don’t think of population averages but instead are just indicating if they have a “good” or “bad” sense of humor.) OK back to demographics. Women were about half as likely to report a sense of humor (Figure 1, p-value < 7.0e-05, OR=0.6) and about twice as likely to report difficulties getting a joke (Figure 2, p-value < 7.9e-09, OR=2.0).

Figure 1. Distribution of responses to the question by sex, “On a scale of 1-5, where 5 is above average, how would you rate your sense of humor?”

Figure 2. Distribution of responses to the question by sex, “How easy is it for you to get jokes?”

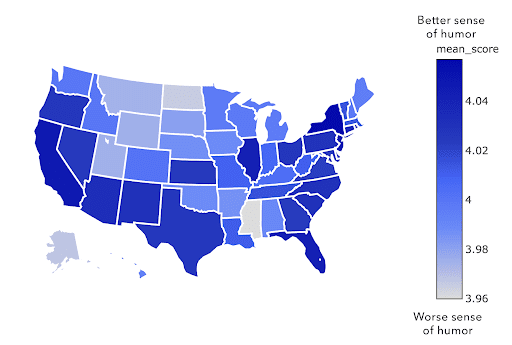

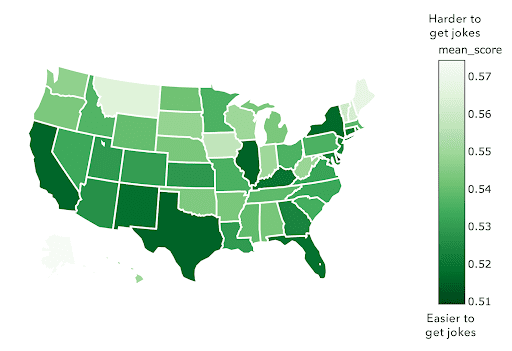

We also found some very small regional variations. People living in the District of Columbia, New York, and California were the most likely to rate themselves as having a good sense of humor, while those in Puerto Rico, Mississippi, and North Dakota were the least likely (Figure 3). As for being able to get a joke, participants from the District of Columbia, Delaware, and Illinois were the most likely, while participants in Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Maine were the least likely (Figure 4). While we did find that the differences between the highest ranking and lowest ranking states were statistically significant (sense of humor p-value = 2.215e-10; gets jokes p-value = 6.372e-12), the mean differences between states are not particularly large.

Figure 3. Regional differences across the US for having a sense of humor.

Figure 4. Regional differences across the US for getting jokes.

To investigate the underlying biology of having a sense of humor and getting jokes, we ran two genome-wide association studies among unrelated Europeans, controlling for age, sex, genetic ancestry, and the version of genotyping platform.

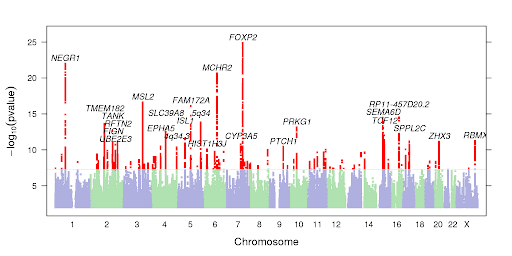

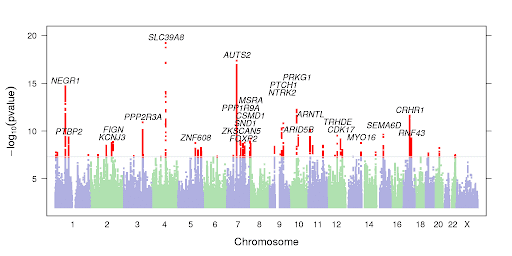

More than two dozen genetic variants reached genome-wide significance, which is indicated in red in Figure 5 for sense of humor and Figure 6 for getting jokes. Red dots show genetic variants that are “statistically significantly” associated with the trait being investigated — in this case, having a sense of humor and getting jokes — which means they’re more likely to be real associations (as opposed to random noise).

Figure 5. Genome-wide association study Manhattan plot for “On a scale of 1-5, where 5 is above average, how would you rate your sense of humor?” n=466,828. A Manhattan plot shows how strong the associations are between a particular trait and different genetic variants (represented by dots). This model treated the responses as linear, and adjusted for age, sex, genotyping platform, and the top five principal components of genetic ancestry.

Figure 6. Genome-wide association study Manhattan plot for “How easy is it for you to get jokes?” n=463,738. This model treated the responses as linear, and adjusted for age, sex, genotyping platform, and the top 5 principal components of genetic ancestry.

This is where it gets interesting. We saw a number of significant genetic associations that overlapped between the self-rated sense of humor and an ability to get jokes. The strongest association for the “sense of humor” trait was within FOXP2, a gene known to be incredibly important for the ability to use language. A number of associations were with other genes somehow involved in brain function: PTCH1 is involved in brain development, SEMA6D is involved in neurodevelopment more generally, and NEGR1 has been implicated in both obesity and intelligence. We also found associations in PRKG1, which is involved in foraging and self-regulation. Foraging and self-regulation are related to goal-directed behavior such as finding and gathering food. It requires recall and pattern recognition, and may come in handy with sophisticated word constructs that make up humor. Another hit was found at SLC39A8, which is involved in the uptake of manganese, an element involved in brain function.

As we said earlier, our researchers also found a strong association between one’s ability to “get jokes” and AUTS2. This gene is known to be important for neurodevelopment and a major player in autism. Some studies have shown that individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome or those with high-functioning autism tend to have a different style of humor, and often don’t laugh at what is commonly found as funny, while laughing at scenarios some don’t believe to be humorous.

So What?

Humor is universal. It’s a way to bond with other people and connect. It’s part of what makes us human. Understanding more about why we are the way we are, how a trait like humor is associated with something so seemingly unrelated like neurodevelopment, only adds to our understanding of what makes us, us. And like all complex behavioral traits, there isn’t a single gene for a well developed funny bone. Rather there are many genetic variants and environmental causes that give us our sense of humor.

Maybe next year at this time we’ll have data not just on the genetics of having a good sense of humor, but on the genetics of pulling a good prank. So this April 1st don’t get caught with your genes down, and get ready to smile.